Fr. Bryan Howard

6th Sunday in Easter– Year C – 26 May 2019 Why should we obey God and why should we obey the Church? The second part of that question is the easier part to answer. We should obey the Church because Jesus founded the Church and gave her the authority to teach in His name. The Church doesn’t claim any authority to change the deposit of faith. We can grow in our understanding of the faith, but we can’t change it. The Catholic Church was founded by Jesus when He told St. Peter, “You are Peter, and on this rock I will build my Church, and the gates of the netherworld shall not prevail against it.” Has the Church made mistakes? Yes, very many. We’ve had Popes, bishops, and priests have given in to every temptation under the sun, but for these 2000 years the Church has protected the deposit of faith that was entrusted to her by the Lord. It has been kept whole an entire not because of the people who make up the Church but because of the Holy Spirit. We don’t have faith in the Church, we have faith in God, and God works through the Church. That brings us to the real question, “Why should we obey God?” The word obedience comes from the Latin words ob, to, and audire, to listen. So, obedience means “to listen to.” Why would we listen to God? First, because He’s all good and all knowing. It’s in our best interest to listen to God because He wants the best for us and can help us get it. St. Thomas Aquinas points out that true and lasting happiness can’t come from pleasure, wealth, honor, or any worldly good. These always leave us wanting, and often turn against us. Only God can satisfy the longing of our souls. However, that’s kind of a self serving reason. God wants to bring us past the fear of punishment and hope for reward; He wants to bring us to love. In today’s Gospel, Jesus tells His disciples, “Whoever loves me will keep my word, and my Father will love him, and we will come to him and make our dwelling with him. Whoever does not love me does not keep my words.” Really think about what that means. When you’re passionately in love with someone you really pay attention to them when you’re with them. You want to look at them, to listen to their voice and what they’re saying. You want to be with them all the time, and, ultimately, to make your dwelling with them. God is courting us. He’s drawing us into a deeper relationship with Himself. He seeks us out, calls to us, gives us grace and light and life, and invites us to “come and see,” as the Lord told the first disciples. We each have to make a choice for ourselves, to believe or not to believe, to live the faith or not to live it, to love God or not to love Him. We can’t put off the choice forever. We know that atheists are people who don’t believe in God, and theists are believe who do believe in some sort of God, but agnostics are people who say that there’s not enough evidence to know. They say that they’re just not sure, so they won’t make a decision one way one the other. However, there’s a time limit. There will come a day when we run out of time. It’s like a ship at sea in a heavy fog. There’s a storm rolling in and they need to make it to a safe harbor before it reaches them are the ship will be capsized, but they can’t tell which harbor is there home port. If you wait too long, then that is a decision, and you’ll just have to take your chances. Is there a God or isn’t there? Is there an afterlife or isn’t there? Not making a choice is the same as choosing not to believe. We have at least two types of evidence to help us to believe. There’s the writings of the great theologians who give us logical reasons and evidence. Then there’s the lives of the saints, who give us an example of the power of the faith. One of these, Pedro Sanz, was born in Asco, Spain in 1680. He went on to join the Dominicans in 1697 and was ordained a priest in 1704 at the young age of 24. He was sent on a missionary journey to the Philippines in 1712 and then to China in 1713, where he would spend the rest of his life. St. Pedro was arrested by anti-Christian forces in 1746. On this day, May 26, 1747, he martyred for the faith and celebrated his heavenly birthday. The viceroy of Peking, one of their captors, wrote about St. Pedro and the other Dominicans held prisoner, “What are we to do with these men? Their lives are certainly irreproachable; even in prison they convert men to their opinions, and their doctrines so seize upon the heart that their adepts fear neither torments nor captivity. They themselves are joyous in their chains. The jailors and their families become their disciples, and those condemned to death embrace their religion. To prolong this state is only to give them the opportunity of increasing the number of Christians.” St. Pedro Sanz’s last words were, “Rejoice with me, my friend; I am going to heaven!” Tomorrow, May 27, is the feast day of St. Augustine of Canterbury, a saint who’s worth knowing something about. He was born in Rome sometime in the 5thcentury and died in Canterbury, England, in 605 AD. He is called the apostle to the English and the Anglo-Saxons. His remains are interred outside the Church of Saints Peter and Paul in Canterbury.

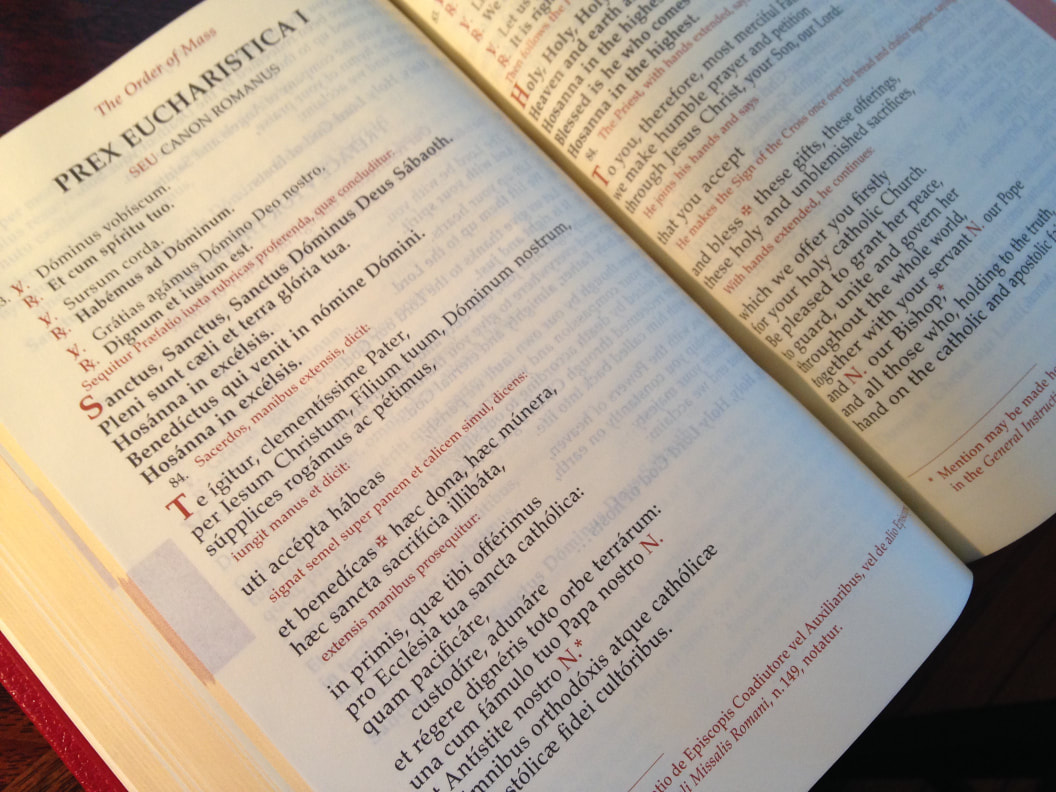

While still living in Rome, Augustine became a monk in the Benedictine tradition and was eventually elected as Abbot of St. Andrew’s Abbey. In the year 597, Pope St. Gregory the Great send St. Augustine and 40 of his monks to evangelize the British Isles. This was a terrifying assignment. The Roman Empire first established a presence in the British Isles 55 BC when Julius Ceasar invaded and conquered the Celtics tribes in the southern part of England, but he was not able to establish a permanent colony there. That wouldn’t happen for another 98 years, when Claudius Ceasar invaded with a large Roman army. Although the Romans were never able to completely conquer the British Isles, the did control most of England and Wales for over 300 years, until about the early 400s, when the Romans were forced to pull back. So, when St. Augustine traveled to Britain it had been over 150 years since the Romans had left Britain, and the rumors of the barbaric celtic tribes that had taken over caused St. Augustine to turn back. When he got back to Rome, however, Pope St. Gregory the Great convinced St. Augustine that he had to go and bring the Gospel to the English, and so he set out again. St. Augustine succeeded in converting King Aethelberht and many thousands of his people, reestablishing the communication between the people of Britain and the rest of western Europe, and establishing the Catholic Church in England. He would soon be ordained as the first bishop and then archbishop of Canterbury. In his 8 years in Canterbury, he worked to spread the Gospel, bring about conversions, and strengthen the bonds between the England and the Roman Church, in union with the Pope. He’s been venerated as a saint for well over 1000 years and is the patron saint of England. Latin is no longer the native language of any one people, but it still has many uses. It’s the language of science, and particularly of medicine and biology, it’s indispensable for studying the history and literature of Europe, and, of course, many English words come from Latin, like domestic, picture, and even the world me. However, probably the most famous use of Latin is in the Catholic Church. Latin is still the official language of the Holy See and of the Vatican, the Pope’s encyclicals, documents of ecumenical councils (like Vatican II), and many official Church pronouncements are all first published in Latin. The official versions of our liturgies, like the Mass and baptisms, are in Latin and translations must be approved by Rome before they can be used. Finally, there are many Church documents, writings of Popes, Church councils, and Church synods, that have simply never been translated, simply because there hasn’t been a big enough need to do so.

Some people will tell you that the Church gave up Latin at the Second Vatican Council, but that’s not what the council actually said. In Sacrosanctum Concilium, published in 1963, the Fathers of the Council said, “The use of Latin, with due respect to particular law, is to be preserved in the Latin Rites,” and, “Nevertheless care must be taken to ensure that the faithful may also be able to say or sing together in Latin those parts of the Ordinary of the Mass which pertain to them” (SC, 36 and 54). Pope St. Paul VI, who was the pope during the end of the Council, said, “The Latin language is assuredly worthy of being defended with great care instead of being scorned; for the Latin Church it is the most abundant source of Christian civilization and the richest treasury of piety…we must not hold in low esteem these traditions of your fathers which were your glory for centuries” (Sacrificium Laudis). Most of the earliest Christians spoke Aramaic and Greek, and the earliest Masses would have been celebrated in those languages. The Bible is written in Hebrew and Greek. Latin, though, was the language of Rome, and Rome was the center of the western Church. The priests and monks who converted most of the world came from Rome and brought Latin with them. They found that the languages of the people they went to convert didn’t have words to convey the language of the Mass, so the Mass stayed in Latin while the people were taught in their own languages. The Church kept Latin because of its beauty, its universality, and its stability. It is stable because it isn’t anyone’s native language. English changes as we need to express new words and ideas, and the meanings of words change over time. Latin doesn’t change, because no one speaks it as their native language, so it helps to preserve the meaning of the teachings of the Church. It is also the same everywhere. Theologians in England, France, Spain, and Italy grew up speaking different languages, but they would have learned the same Latin in school, so they can communicate with each other. Latin is also beautiful. Many other languages are beautiful, too, but the cultural history of the Church, its music, literature, and poetry, is mostly in Latin. Having Mass in the language that we speak every day has allowed us to understand the prayers that the priest is praying and to understand what is happening, but hearing the Mass in a language we don’t speak every day, especially Latin, reminds us that the mass isn’t ordinary and normal, but extraordinary and mystical. I’m not saying that you should start going to Mass in Latin every week, or that we’re going to switch to Latin Mass at Lourdes, but I am encouraging you to experience Mass in Latin at least sometimes, to be reminded that something amazing is happening in front of you.

If you go into just about any Catholic Church or home in the world, you’ll find the images of Jesus, the Blessed Virgin Mary, and the saints and angels, but if you go into a protestant home or church, a Jewish home or synagogue, or a Muslim home or mosque you probably won’t find images of God or the saints. They all believe that these images are idolatrous and basically equivalent to worshipping images as gods. Why is that, and how do Catholics use images?

Those who are against images point to Exodus 20:4-5 as their proof, which says, “You shall not make for yourself a graven image, nor a likeness of anything that is in heaven above or on earth below, nor of those things which are in the waters under the earth. You shall not adore them, nor shall you worship them.” This read this as saying that we shouldn’t make any images of God, angels, humans, or animals because of the possibility that we might be tempted to worship them. However, if we look just 5 chapters later in the book of Exodus, we find God telling Moses how to build the tabernacle, “Likewise, you shall make two Cherubim of formed gold, on both sides of the oracle. Let one Cherub be on the one side and the other be on the other. And let them cover both sides of the propitiatory, spreading their wings and covering the oracle, and let them look out toward one another, their faces being turned toward the propitiatory, with which the ark is to be covered” (Ex 25:18-20). If God didn’t want us to make any images of anything “in heaven above,” then why did he command Moses to make these images of angels? The Catholic, and original Christian, interpretation of Exodus 20 is that God doesn’t want us to make any images that are meant to be worshiped, or to worship any images. The Second Council of Nicaea in 787 officially approved and regulated the use of images. Images of God or the saints are to receive veneration, they are to be respected and should not be treated with disdain or disrespect. They should not, however, be worshiped and adored, as worship and adoration are reserved for the person of God Himself. So, the Eucharist, which is the real presence of Jesus Christ, is to be worshipped and adored, and so we may kneel or even lay prostrate before Him present in the Most Blessed Sacrament, but a statue of the Sacred Heart should only be venerated. The purpose of images is to call to mind the person, event, or idea that it represents. We can make an image of Jesus Christ because Jesus became man, and we can make an image of His human nature, and that image reminds us that God is always present with us and raises our minds and souls to worship God Himself. The images of our Blessed Mother, the saints, and the angels also make us think of those people, of their lives, of how they are alive in heaven and can pray for us, and can motivate us to imitate their holiness in our lives. Just as the cherubim on the tabernacle weren’t thought to be real angels but only represented the cherubim who worship God constantly in heaven, so the images that we keep in our churches and homes and even in our cars (like those visor clips with the St. Christopher medal) can lead us to contemplate the realities that they represent and so draw us closer to God Himself. Here in southern Louisiana we spend more time in nature than people do in many places. We enjoy and use nature when we hunt, fish, spend time in the wild, and live off the land. However, we also understand, better than many, the need to care for the land. Due to neglect and coastal erosion some of the bounty our fathers and grandfathers enjoyed is gone, and we’ve had to take steps to protect what remains. Since we just passed Earth Day on April 21 and Arbor Day on April 26, we should look at how the Church calls us to treat the world around us.

After God created the world, the animals and humanity, “God saw all the things that he had made, and they were very good.” After God made man and woman, he said, “God blessed them, saying: Increase and multiply, and fill the earth, and subdue it, and rule over the fishes of the sea, and the fowls of the air, and all living creatures that move upon the earth.” The earth and nature are good and they are gifts from God. God has commanded us to both fill the earth and subdue it. The Hebrew word for rule means literally “to tread under your feet,” as in treading grapes to make wine. We are given rule of the Earth so that we can make it serve our needs by cultivating it and using the produce of the land. However, the command to subdue the earth is connected to the command to “fill” it through having children. We are stewards of the earth, and we must protect it so that future generations will have all the good things of the land that we have. In 2008, Pope emeritus Benedict said, “Respecting the environment does not mean considering material or animal nature more important than man. Rather, it means not selfishly considering nature to be at the complete disposal of our own interests, for future generations also have the right to reap its benefits and to exhibit towards nature the same responsible freedom that we claim for ourselves.” We have to stay away from the two extreme views. There are those who actually believe that animals and plants are more important than people. They don't just want to reduce the human population, they want to eliminate it, believing that our absence will allow the environment to flourish. On the other hand, there are those who wantonly violate and destroy nature for their own personal gain by polluting, destroying, and misusing it. They don't care about their responsibility to be good stewards of the gifts of the earth or about their responsibility to future generations. God has given us the freedom to use creation for our own benefit, for our families, and for our communities, but He requires us to use it responsibly. We must consider how our actions affect the people around us and future generations. Those in positions of authority in government have a responsibility to put in place laws and programs that protect creation for ourselves and future generations while at the same time respecting the right of people to use nature responsibly. Those in the business world have a responsibility to steer their companies towards uses of creation that consider the good of the entire community and not just one person or company. Parents have a responsibility to teach their children respect for the natural world so they can enjoy it safely and responsibly. All individuals have a responsibility to respect creation as well, even it is by simply cleaning up your camp site or not littering. Remember, Christ taught us that power means the power to serve others, not to be served. Even in how we treat creation, we must try to be of service to others, and not expect them to serve us. Link to Dies Domini

Fr. Bryan Recommends The Apostolic Letter Dies Domini In 1998 Pope St. John Paul II wrote an apostolic letterto the bishops, clergy, and faithful of the Catholic Church throughout the whole world called Dies Domini, which means The Lord’s Day, on keeping the Lord’s Day holy. Have you ever wondered why we have to go to Mass on Sundays? The Old Testament tells us to keep the Sabbath holy, but the Sabbath is on Saturday, not Sunday. Plus, we have Mass every day of the week. Even if we do have to go to Mass every week, why not Friday, the day on which Jesus was crucified, or some other day, or why not just let us pick a day ourselves? As St. Jerome said over 1,500 years ago, “Sunday is the day of the Resurrection, it is the day of Christians, it is our day.” In this letter the Pope explains why Sunday, the Lord’s Day, is the “lord of days.” He explains that Sunday is a celebration of the work of Creation, as it’s the day God began the work of creation. The original Sabbath was a celebration of the first creation, since God rested on the seventh day, Saturday, but the new Sabbath is Sunday, the first day, because in the Cross and Resurrection of Jesus God is doing something new in the world, a new creation. He explains that Sunday is not only the day of the Resurrection, not only the eight day, the day of the new creation, it is also the day of the Holy Spirit. Pentecost, the day when the Holy Spirit descends upon the disciples in tongues of fire, happened on a Sunday, exactly 50 days after the Resurrection of Jesus. In the Pentecost the Church was born from the fires of the Holy Spirit, and so the Church comes together on Sundays to be renewed and re-born in the Holy Spirit. The Pope explains what it means to keep the Lord’s Day holy. He reminds us that Sunday is a day of joy, a day of solidarity with family, friends, and community, and a day of rest from servile labor. The heart of keeping holy the Lord’s Day, however, is the Sunday Mass. As Pope St. John Paul II wrote, “For this presence (of the Risen Lord) to be properly proclaimed and lived, it is not enough that the disciples of Christ pray individually and commemorate the death and Resurrection of Christ inwardly, in the secrecy of their hearts. Those who have received the grace of baptism are not saved as individuals alone, but as members of the Mystical Body, having become part of the People of God. It is important therefore that they come together to express fully the very identity of the Church, the ekklesia, the assembly called together by the Risen Lord who offered his life ‘to reunite the scattered children of God’ (Jn 11:52).” |

AuthorFr. Bryan was pastor of Our Lady of Lourdes from July 3, 2017 to June 2022. Categories

All

Archives

June 2022

|

||||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed