|

Question: Is making the sign of the Cross an act of prayer?

Answer: This was more of a recommendation for an article than an actual question, but let’s take the opportunity to reflect on the Sign of the Cross. We make the Sign of the Cross when we enter and exit Church, when we cross in front of a Church, at the beginning an end of prayer, and probably more times that I’m forgetting. Making the Sign of the Cross reminds us that we’re in the presence of God, calls to mind the central mysteries of the faith, and prepares us to pray. In fact, it is itself a prayer and something that we shouldn’t just take for granted. The three central mysteries of the faith are the Holy Trinity, the Incarnation, and the Paschal Mystery, and all three of them are called to mind when we make the Sign of the Cross. We literally sign our bodies with the Cross. The Cross is the instrument through which the Lord offered His life to the Father for our salvation, and so the Cross has come to represent our salvation through the death and Resurrection of the Lord. Signing ourselves with the Cross shows that we belong to Christ. In the Rite of Baptism the priests, parents, and godparents sign the infant on the forehead with the sign of the Cross as the priest says, “N., the Church of God receives you with great joy. In her name I sign you with the Sign of the Cross of Christ our Savior.” Likewise, bearing the Cross is the sign of a follower of Christ, as the Lord said, “Whoever wishes to come after me must deny himself, take up his cross, and follow me (Mk 8:34).” The Cross of Christ also points to another great mystery of faith, the Incarnation. The Lord was only able to take up His Cross and be nailed to it because He had already taken on a human nature. In Himself, God is impassable, meaning unable to suffer, because He is pure existence in Himself. In the Incarnation the Son of God, coequal with God, took on a human nature without ceasing to be God. The person of Jesus Christ is both God and man; as man He is able to suffer the death of the Cross, and as God He was able to transcent the grave. As man He was able to offer atonement for our sins, and as God He is able to make the perfect offering of Himself. As St. Paul wrote, “Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not consider equality with God something to be seized. Instead, he emptied himself, taking the form of a servant, being made in the likeness of man, and accepting the state of a man. He humbled himself, becoming obedient even unto death (Phil 2:5-8).” Every time we make the Sign of the Cross we invoke the Most Holy Trinity, showing that we are speaking and acting “in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.” We call on God Himself and recognize that God is three person united in one Divine Nature. The Sign of the Cross shows that the three great mysteries of the faith, the Trinity, the Incarnation, and the Paschal Mystery of Christ’s death and Resurrection, are all united in the one Mystery of the Faith. When you make the Sign of the Cross and call upon the Holy Trinity bring all of this to mind. Thank the Lord for the gift of salvation through His death and Resurrection, praise the Lord for His awesome Incarnation, and life your thoughts to God Himself. ANNOUNCEMENT: Once a month I’ll write an article answering a question from a parishioner on the Church, the Mass and sacraments, the Bible, the Blessed Virgin Mary and the Saints, spiritual theology, or anything related to Christianity. Either write your question down and put it in the collection basket, or email me at [email protected].

0 Comments

You may have noticed that we recently added a veil, basically a white curtain, to the tabernacle. My mom actually made the veil with material left over from my Marian chasuble and some lace that she made. Aside from being beautiful, why should we have a tabernacle veil? A Vatican document from 1967 tells us the purpose of a tabernacle veil, “Care should be taken that the presence of the Blessed Sacrament in the tabernacle is indicated to the faithful by a tabernacle veil or some other suitable means prescribed by the competent authority” (Eucharisticum Mysterium, 57). The idea of the tabernacle veil goes back to the Old Testament, and that history can shed light on the Mass and the Eucharist.

In the book of Exodus the Lord tells Moses how to make the Tent of Meeting, called the Tabernacle, to be a place for the people to worship God and offer sacrifice to Him. The Temples in Jerusalem were copies of this original design. The innermost room was the Holy of Holies and was reserved for the High Priest, who could only enter it once a year on the Day of Atonement. The Ark of the Covenant was kept in the Holy of Holies. The Ark was a symbol of God’s covenant faithfulness to the people of Israel and was considered to be like a throne for God. The lid of the Ark was called the “Mercy Seat.” There was a veil separating the Holy of Holies. The veil represented the presence of God because this place, the Holy of Holies, was set apart for the Lord God. The entire Temple was God’s house, but the Holy of Holies was the holiest part of the Temple. At the moment of Christ’s death on the Cross, the veil of the Temple was torn down the middle (Mt. 27:50-51). Why was the veil torn? Jesus Christ is the true Temple (Jn 2:21), the true presence of God on Earth. When Christ gave up His Spirit, the Spirit of God also left the Temple in Jerusalem because the True Temple had been destroyed. The veil was torn as a sign that God was no longer present in the Temple. However, Christ has been raised from the tomb and has ascended to heaven, and He’s left us the Mass as the memorial of His Cross and Resurrection. In every Mass the Spirit of God descends and changes (through Transubstantiation) the bread and wine into the Body and Blood, Soul and Divinity of Jesus Christ. After Mass, the consecrated hosts are placed in our own Tabernacle, which houses the True Presence of God. The veil in the tabernacle is a sign that God is truly present there, but that veil is drawn back during every Mass as a sign that faithful followers of Christ will share His presence forever in heaven. Have you ever wondered why Catholic churches are designed the way they are? In the earliest days of the Church Christianity was under nearly constant persecution. First, the Jewish officials were trying to get the apostles and disciples of Jesus Christ to stop preaching about the Resurrection. Then, in the 60’s AD, the emperor Nero Caesar started the Roman persecution which would continue, with some interruptions, until the emperor Constantine legalized Christianity in 313 AD (although the persecutions didn’t end immediately in every part of the empire).

Suddenly, after over 250 years of persecution, Christians could practice their religion openly and didn’t have to gather in people’s homes or the catacombs to celebrate Mass. The very first Churches during this time were converted from public buildings and meeting areas, but soon the Church in Rome was building the first great basilicas. These Churches took inspiration not only from Greek and Roman architecture but also from our Jewish roots. The first holy places were on mountains. When the Israelites were freed from slavery in Egypt, the journeyed to Mt. Sinai where they offered sacrifices to God and received the Ten Commandments and the Mosaic Law. In the first book of Kings, the Prophet Elijah flees from King Ahab to Mt. Horeb where he encounters God. Also, Solomon’s Temple was build on Mt. Zion, in Jerusalem, which was considered to be a sacred mountain. That’s why Psalm 24 says, “Who shall ascend into the mountain of the Lord, or who shall stand in His holy place?” The mountain of the Lord is Mt. Zion, and the “holy place,” or sanctuary, is the Temple. When Solomon built the Temple it was designed as a sort of artificial mountain. When you went up to the Temple to worship you would first ascend a flight of steps from the Outer Court to the Upper Court, which housed the bronze altar of sacrifice. Only the priests and Levites could enter the Upper Court. You would then go up another flight of steps into the Holy Place which housed the altar of incense, ten lamps stands, and a table holding bread (The Bread of the Presence) and wine. Finally, you would then ascend another flight of steps into the Holy of Holies, which was blocked off by a veil and housed the Ark of the Covenant. The Ark was a symbol of Jesus, since it contained the tablets of the Ten Commandments and a jar of the Mana that the Israelites ate in the desert after the Exodus and which was a symbol of the Eucharist. If you look at the picture of St. Louis Cathedral in New Orleans, you can see how traditional Catholic churches are modeled after Solomon’s Temple. You would first ascend into the Church itself, where the people gather for Mass. Then, you ascend another flight of steps into the Sanctuary, or Holy Place, which has the ambo for the readings and the celebrant’s chair. Then, you ascend a final flight of steps to the tabernacle, which contains the Eucharist, the Body of Christ, just like the Ark in the Holy of Holies was a golden box containing the Mana. You further you go into the Church, the more you are ascending the “mountain of the Lord” and the closer you are getting to Jesus. Ultimately, the sacred mountains in the Bible, Solomon’s Temple, and our Catholic Churches all point to something beyond themselves. They point us to heaven. Our goal in life should be to grow closer to God that we might one day ascend to heaven to be with Him for eternity. Why are the sacraments important? What do they do? How do they affect us? The sacraments are symbols of the grace of God that was won for us by Christ on the Cross and that comes into our lives through the Holy Spirit, but they aren’t merely symbols. Since the sacraments were instituted by Christ Himself, they have His authority and carry His power. When the sacraments are performed in the proper way they really bring about what they symbolize. They don’t rely on the holiness of the one performing the sacrament; they rely on the promise of Christ.

Certain sacraments can be received many times, like the Eucharist and Confession, because they give us graces that we need over and over, like the nourishment of God’s grace and the forgiveness of sins. Other sacraments can only be received once, like Baptism, because they give us a grace that tends to stay with us. The Catechism of the Catholic Church says this: The three sacraments of Baptism, Confirmation, and Holy Orders confer, in addition to grace, a sacramental character or “seal” by which the Christian shares in Christ’s priesthood and is made a member of the Church according to different sates and functions. This configuration to Christ and to the Church, brought about by the Spirit, is indelible; it remains for ever in the Christian as a positive disposition for grace, a promise and guarantee of divine protection, and as a vocation to divine worship and to the service of the Church. Therefore these sacraments can never be repeated. (CCC, 1121) This seal is permanent. Once someone is baptized, confirmed, or ordained, they are forever baptized, confirmed, or ordained. Since the mark or seal is on the soul it lasts even after death. This seal confirms us to Christ and especially to His Cross and Resurrection. It is a “disposition for grace” and a “promise of divine protection.” God wants to give us grace to protect us against spiritual evils and the activity of the devil and to help us to grow in holiness, but we still have to accept those graces and cooperate with how God wants to work in our lives, which the sacramental seal helps us to do. Finally, the seal is a “vocation to divine worship and to the service of the Church.” In other words we’re called to make use of the grace that we’ve been given. This grace adheres or sticks to the soul and it’s difficult to get rid of. So we have to ask ourselves, “How am I using the grace of Baptism that I received? The grace of Confirmation? The grace of the diaconate or priesthood?” If you’ve been around the Catholic Church very much, then you’ve surely noticed a priest imposing hands over or laying hands on some object or person, for example, when he’s blessing something or someone, or in the sacraments. In the Mass the priest holds his hands over the bread and wine during the epiclesis of the Eucharistic Prayer, in the ordination of a priest or deacon the bishop lays his hands on their heads before praying the Prayer of Ordination, and in the Sacrament of Reconciliation the priest holds his hand over the person while praying the Prayer of Absolution. This is a symbol of the priest calling down the Holy Spirit to give grace, as we read in the Acts of the Apostles, “Then they laid their hands on them and they received the Holy Spirit” (Acts 8:17). So, extending the hands in blessing is a priestly act of calling down the Holy Spirit, but what is that blessing actually doing for us.

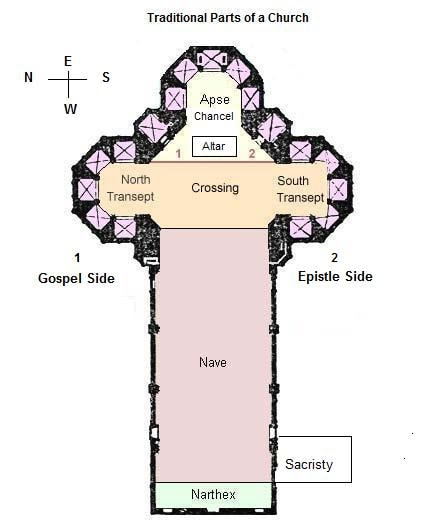

The first blessings we see in the Bible occur in the Book of Genesis. We see Isaac blessing Jacob and Jacob blessing his children and grandchildren. The blessings in Genesis are of fathers blessing their children, as when Isaac blesses Jacob and makes him his primary heir. A blessing can also make someone who isn’t your child into your child. The 12 tribes of Israel are the sons of Jacob, whose name God changed to Israel, except that the rest of the Bible often speaks of the half-tribes of Ephraim and Manasseh. These were Joseph’s two sons, who received a special blessing from Israel, and from that point on they were listed with the sons of Israel instead of his grandchildren. In the book of Judges we read about Micah, who set up a shrine in his land and was looking for a priest for the shrine. One day, a Levite, the priestly tribe, was passing through, and Micah asked him to stay and be their priest, saying, “Stay with me, and be to me a father and a priest, and I will give you ten pieces of silver a year, and a suit of apparel, and your living” (Jdg 17:10). So, a priest, in the Old Testament, is seen as a type of spiritual father. This continues in the New Testament, when St. Paul calls himself a father to those whom he has brought into the faith, “For though you have countless guides in Christ, you do not have many fathers. For I became your father in Christ Jesus through the Gospel” (1 Cor 4:15). In both the Old and New Testaments, the one who blesses, the priest, is considered a spiritual father, because through the blessing of God we become children of God. In the Sacraments, whenever the priest imposes hands over something he calls down the Holy Spirit and that thing changes. In the Mass, the Holy Spirit, changes the bread and wine into the Body and Blood of Christ. In the Sacrament of Holy Orders, a man becomes a deacon, priest, or bishop. In the Sacrament of Reconciliation our sins are forgiven and our souls cleansed. In Baptism the priest lays his hand on your head, you are reborn through water and the Holy Spirit, and you become a child of God. If, then, we are children of God, let us follow the Son of God, Jesus Christ our Lord, in the way we live our lives.  Everything about the Mass means something, and that includes the building that we celebrate the Mass in. Basic church architecture comes from the ancient period, especially during the 4th century after Christianity was legalized, and it was refined during the High Middle Ages. They tried to design the Church to speak to us of the faith and teach us about God just by seeing it. First, the Church buildings represents the Church itself. Of course, the Church is more than a buildings or a charitable organization. The Church is the body of Christ, with Jesus Christ as the head of the Church and we, the faithful on earth, along with the souls in purgatory and the saints in heaven, are the members which make up the body. In a Church building the sanctuary, where the altar, celebrant’s chair (cathedra), and tabernacle are is the head and represents Jesus. The altar is connected to Jesus because it is on the altar that the Eucharist, the Real Presence of Christ, is offered to God the Father. The celebrant represents Jesus because He presides over the Mass in persona Christi, in the person of Christ, by using Jesus’ words and actions at the Last Supper to offer the sacrifice of the Mass. The tabernacle, of course, holds the Eucharist, which is the presence of Jesus Himself. The nave of the Church represents the body of Christ, including us on earth, the angels, and the saints. The nave has the pews and is where the people gather to attend Mass. It also usually has images of the saints in stained glass windows and as statues. If you look at an image of a Medieval Church you’ll see that it even has arms, like a body. The Church also represents heaven and earth. This goes all the way back to Solomon’s Temple. The Sanctuary of the Temple was decorated with angels and represented heaven, while the rest of the Temple was decorated with gardens and animals representing the Earth. In a Catholic Church the sanctuary is where Jesus is, where the offering takes place, and is often decorated with angels, like St. Louis Cathedral downtown. The nave represents earth and is where we are gathered for the Mass. During Mass we look towards the sanctuary, just like we ought to have our eyes fixed on heaven. When it’s time to receive Communion the priest and ministers bring the Eucharist down to the nave, symbolizing the Incarnation, when Jesus came down from heaven to earth, and the people go up towards the Sanctuary, showing that heaven is our final destination. That point where the sanctuary and nave meet, where the altar rail would be in a traditional Church, represents the meeting of heaven and earth both in the person of Jesus Christ and in the Mass. Whenever I go into a Church for the first time, I pay the most attention to the tabernacle, the altar, the stained glass windows, and the stations of the Cross. Look around in churches, look at the details, designs, and artwork in the Church, and ask how this Church is pointing us towards heaven. The Feast of the Assumption was last Thursday, although we celebrate it on the Sunday in the US and many other places to make it easier for people to participate. On the Ascension Jesus ascended to heaven in His body. Of course, as God, Jesus was never not in heaven, because God is everywhere. Jesus didn’t stop being God when He became a man. When He was born of the Virgin Mary, was baptized in the Jordan River, suffered on the Cross, and descended to the realm of the dead, He was also everywhere else in the universe as the second person of the Trinity. God is not limited by anything, even by space and time. However, Jesus is also human, and so, in His humanity, He is limited by space and time, and it was in His humanity, His human body, that Jesus Christ ascended into heaven.

Think about the fact that Jesus, and Mary, His mother, are physically in heaven. When the saints die and go to heaven, they go to heaven spiritually, not in their bodies. We bury the body as a sign of faith that, where Jesus has gone before, the faithful will follow after. Jesus was baptized in the Jordan River and publicly proclaimed as the Son of God, so we are baptized and become children of God. Jesus died, and so we die. Jesus rose from the dead, and so we believe that we will rise from the dead at the end of time when Jesus comes again to judge the living and the dead and the world. Jesus ascended to heaven in His body, and so we believe that we will be brought into heaven in our bodies. There are many people who, for one reason or another, can’t be buried in Christian ground. That doesn’t mean that they won’t be resurrected in the body and raised to heaven; God will be able to find our bodies wherever they end up. However, burial in holy ground is a powerful symbol of trust in Jesus. When we bury someone we are professing our faith that Jesus will raise them up again. The Church even asks us to bury the remains after a cremation, which is allowed as long as it’s not done as a rejection of faith in the Resurrection; after all, we all end up as dust and ashes anyway. Still, Jesus Himself was buried, but He overcame the grave. May God give us a stronger faith in the Resurrection and ascension of Jesus, that we may be confident that He will overcome our graves, too.  Why do we use water to bless ourselves when we enter Church and to sprinkle in our homes, cars, places of business, etc.? We know that we need to use water for baptisms, but how did the Church start using separate, blessed holy water for these other things? After all, in the earliest times of the Church baptisms took place in rivers, streams, and lakes, so they didn’t have baptismal fonts full of holy water in their churches. In fact, since Christianity was illegal, they didn’t even have churches in most places. The Church probably used holy water from the earliest days since water was used in Jewish homes for purification, and the earliest Christians were mostly Jews. However, the earliest recorded use of holy water is from the fourth century. It’s a blessing of water to protect from disease, evil spirits, and all maladies. As soon as Christianity was legalized, churches began keeping the water from baptisms for people to use throughout the year. In the seventh century we begin to have records of churches keeping water at the entrance of the Church for people to bless themselves with or to take home with them. Today, we use holy water for basically the same reasons. We bless ourselves, our homes, and our religious articles with holy water to ask God to purify them, to protect them from demonic influence, and to bestow His grace on them. When we bless ourselves with holy water whenever we enter Church, we’re doing at least two things. First, we’re reminding ourselves of our baptism, through which we first entered the Church and became children of God. Second, we’re asking God to purify us of sin and fill us with His grace. We recognize that we’re entering a holy place and ask God to make us worthy to enter his house. Holy Water is a sacramental, not a sacrament. Sacraments, like baptism, work in and of themselves because of the power that God has given them. Sacramentals require the faith of the person using them to have an effect. If we just bless ourselves with holy water without really thinking about it, but just because that’s what we always do, then it’s not having much of an effect. So, every time you enter a Church and bless yourself with the holy water, ask God to stir up the graces of baptism in your soul, to forgive your sins, and to fill you with His lifegiving grace.  The burning of incense at Mass is a traditional Catholic practice that is used more or less by each priest. Here at Lourdes, we tend to use incense on Holy Days of Obligation and other important feasts, as well as at most funeral Masses, although I never us incense at the 9:00 AM Mass to leave it available for people who are allergic to incense. Some people like the incense, and some people don’t like, but whether we like it or not is beside the point. We use incense because it is a truly ancient tradition going back even before the time of Christ into Old Testament times. We read in the book of Exodus that God told Moses to have an altar made for the burning of incense. It says, “And you shall put it before the veil that is by the ark of the testimony…and Aaron shall burn fragrant incense on it every morning…and when Aaron sets up the lamps in the evening he shall burn it, a perpetual incense before the Lord.” (Ex 30:6-8). The Israelite priests would burn incense before the Ark of the Covenant twice every day as an offering to the Lord. The burning of incense, and the smoke rising up, represent our prayers rising up to God. The book of Revelation says, “And when he had taken the scroll, the four living creatures and the twenty-four elders fell down before the Lamb, each holding a harp, and with the golden bowls full of incense, which are the prayers of the saints” (Rev 5:8). Psalm 141 says, “Let my prayer be counted as incense before thee, and the lifting up of my hands as an evening sacrifice.” The incense also represents the presence of God. In the Bible God’s presence is seen as a cloud. When the Lord descends upon Mt. Sinai to give Moses the Ten Commandments, a cloud envelopes the mountain. When Jesus takes Peter, James, and John up Mt. Tabor, God the Father speaks to them from a cloud. The First Book of Kings records what happened when King Solomon dedicated the first Temple, “And when the priests came out of the holy place, a cloud filled the house of the Lord, so that the priests could not stand to minister because of the cloud; for the glory of the Lord filled the house of the Lord” (1 Ki 8:10-11). We use incense at Mass, in Eucharistic processions, and in Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament as a visible reminder that God is present among us. In the Mass we incense the altar, the Book of Gospels, the priest, the people, and the Eucharist, because God is present in His Church, in His Word and in His priest, and in His people, and God is sacramentally present in His Body and Blood. That incense represents the prayers, worship, and praise that we offer to God, that they may rise up to the Lord and be pleasing to Him.  Since today is the Feast of the Baptism of the Lord, I’ve been thinking a lot about baptism. John the Baptist said about Jesus, “I baptize you with water for repentance, but he who is coming after me is mightier than I, whose sandals I am not worthy to carry; he will baptize you with the Holy Spirit and with fire” (Mt. 3:11). The only thing necessary for baptism is to use real water, to intend to do what the Church intends, and to use the formula, “I baptize you in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.” However, there are other rites and symbols in a Catholic baptism which the Church uses to show us what’s happening in baptism, such as the water, the white garment, and the candle. Water is necessary for the baptism to be valid, but it isn’t used on accident. We use water because water does physically for the body what baptism does spiritually for the soul. Water is used to clean things because almost everything dissolves in water, and baptism “cleans,” or purifies, the soul since it removes all traces of sin, both personal sin and original sin. Water is also necessary for life. We need to drink water to live, our bodies are filled with water, and we are born from water. In baptism, we’re reborn through water into the family of God and given the new life of the Holy Spirit. After the person is baptized they are clothed in a white garment. As this is done the celebrant prays, “You have become a new creation, and have clothed yourself in Christ. See in this white garment the outward sign of your Christian dignity…bring that dignity unstained into the everlasting life of heaven.” This visibly shows the cleansing of the soul that happens in baptism and reminds us not to stain ourselves by falling back into sin. Then someone, usually one of the godparents, lights the baptismal candle from the Paschal Candle, which is lit for every baptism. The Paschal Candle, or Easter Candle, represents the resurrected Christ. At the Easter Vigil Mass the Paschal Candle is lit outside and then brought into the Church in procession, representing Jesus Christ returning to the Church after His death on the Cross on Good Friday. As St. Paul tells us, “Do you not know that all of us who have been baptized into Christ Jesus were baptized into his death? We were buried therefore with him by baptism into death, so that as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, we too might walk in newness of life” (Rm. 6:3-4). The baptism candle therefore represents the Resurrection of Jesus Christ giving new life to the soul of the baptized and the hope for our own resurrection to eternal life in heaven. There are other rites in the Rite of Baptism, like the two anointings and the ephphatha (and yes, that’s spelled correctly), but I chose to reflect on these three to show us that baptism is supposed to be about being cleansed of our sins and anything that is not of God and receiving the new life of the Holy Spirit. May we all live out the grace of baptism in our lives. |

AuthorFr. Bryan was pastor of Our Lady of Lourdes from July 3, 2017 to June 2022. Categories

All

Archives

June 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed